ACUFO-1944-11-23-BELGIUM-1

The first appearance of the 1944 story of the “Phantom Fortress” in the ufology literature is in one of the monographs that the US ufologist Loren E. Gross compiled.

In his self-published “Mystery of UFOs - A Prelude”, in 1971 - 1973, he told that on November 23, 1944, a US Army Air Force B-17 swooped down to make a sloppy emergency landing close to a British anti-aircraft battery in a Belgium field. The British gunners rushed up to the downed bomber to rescue the crew but were greatly puzzled to find no one aboard. The bomber had apparently landed itself, something that was not unknown to happen once in a while after being abandoned in the air if conditions are right. After turning off the engines by experimenting with the controls, the soldiers examined the plane's interior and found out that the crew had bailed out of the seemingly undamaged plane. Moreover the solider were astounded to discover all ten of the crew's parachutes still in the aircraft.

Circa 1999, Belgian “skeptical” ufologist Godelieve van Overmeire told that on November 23, 1944, south-west of Brussels in Belgium, according to a letter written by John V. Crisp, part of the entourage of a British officer, who wrote notes during his stay at The Cottage, West-End, Essendon, Hertfordshire, England, transmitted to the authorities through the US Embassy in London:

“On November 23, 1944, the men of the British anti-aircraft unit located a few miles southeast of Brussels, a B-17 Flying Fortress, approaching their firing site. It had its landing gear down and was rapidly losing speed. The British immediately called Troop Commander and almost at the same time the B 17 landed in a plowed field, near the machine guns, bouncing on the uneven ground 30 yards from the anti-aircraft position. At the last moment the tip of a wing touched the ground, sank into it, spinning the plane. The propeller of the nearest engine was thrown in the air, but the other three engines were still running. The gunners were waiting to see the crew come out and welcome them, but no one came out. They went to circle the plane and noticed no signs of life. It was at this point when the Troop Commander called me to the operations room at Erps-Kwerps near Kortenberg. Within 20 minutes I was on site examining the B-17. I had never had to deal with airplanes, but finally I could enter through an entrance under the fuselage. The plane was empty of occupants, yet traces of presence were everywhere. I got into the pilot's seat to stop the three engines which were still running, which succeeded after several attempts. On the navigator's console the logbook was open and the last words written there were “Bad Flack” (vog's note: two possible translations “bad bulletproof vest” or “bad anti-aircraft shot”). With curiosity I retraced the route which was to take the plane from the Ruhr (Germany) to Hertfordshire (England) and I wondered what could have happened to the crew. We all started searching systematically and our most extraordinary find was made in the fuselage where we found a dozen parachutes well folded and ready for use. This made the question about the crew even more mysterious. The Sperry (for tracking bombs) was still in the nose, having suffered no damage and its cover was neatly folded next to it. Behind the navigator's desk there was the Code book giving the numbers and letters of the day for identification. Several pilots' furry jackets were in the fuselage along with a few chocolate bars, some of which were partially eaten. No damage could be discovered to the B 17 apart from that of the landing. So I left directly for the 83rd Tactical Air Force in Everberg to give them my report and the B 17 logbook, several navigation charts, but the story of the landing of a B 17 empty of occupants is remained a mystery to this day. The crew was never found.”

Overmeire said the sources are “GESAG” - a Belgian ufology group - and Martin “Cardin” [sic, Caidin], in his book “Flying Forts” of 1968.

The story of course also appeared in non-ufological sources, and the actual facts are quite different, without any connection to the UFO topic.

A B-17G, serial number 43-38545, of the 401st Bombardment Squadron of the 91st Bombardment Group, based at RAF Bassingbourn was part of a raid on November 21, 1944, on the Synthetic Oil Plant of Merseburg, Germany, during the infamous “Black Thursday” raids on Germany. It was the 3rd mission of this B-17G. The crew was 1st Lt. Harry R. DeBolt as first pilot on his 33rd mission, Major Klette as navigator, Osborne Stone, Bill Dominguez, Dick Cusson, Troy Young, John Alba, Granville Houchins, Chas Walker, and Nelson Richardson.

In the raid, with bomb bay doors open, the B-17 stalled and dropped out of formation, and it was at this instant attacked by enemy fighters, and also began the run through a very heavy and accurate flak barrage. Due to malfunction with the bomb release mechanism, the bombs would not drop, and this caused the aircraft to fall further out of formation. About this time it took the blast from a flak burst just below the bomb bays.

The explosion caused the bombs to drop but No. 2 engine was completely out and No. 3 engine was badly milling and causing undue vibration throughout the aircraft, this being caused by flak damages. At 1500 feet the other two engines failed. The crew began jettisoning all surplus equipment in an effort to lighten the Fortress as DeBolt set course for home. The plane was losing altitude and was turned to a heading of 270° West for friendly lines. The crew stayed with the plane as long as they could, and when it was down to 2,000 feet, DeBolt gave the signal for everyone to “bail-out” and they did, while the B-17 continued on its way with the autopilot on.

All parachutes opened and the crewmen landed in a German occupied part of Belgium. The hid in an abandoned school for a few days, and were then picked up by British infantrymen.

The damaged B-17 continued, losing altitude and remaining in a perfect landing attitude. It amazingly made a perfect three point landing, ground looping at the end of the field and staying there with engines still running, in Huldenberg, about 10 miles east of Brussels, near Liege, Belgium, not far from a British Anti-Aircraft artillery site. A British officer, Major John B. Crisp, ran out to help the crew, but was astonished to find no one on board. He inspected the B-17, and managed to turn off the operating engines.

The B-17 was salvaged. Stars and Stripes magazine published the story on December 8, 1944, and called DeBolt's B-17 - a “Ghost Ship”, or “Phantom Fortress”.

A plane landing almost correctly without a pilot onboard may seem extraordinary. But he plane was on autopilot, as bail out procedure requires, the autopilot makes the plane stay level, and though this is no guarantee of safe landing, though this is of course improbable, there were so much similar situations during WWI that there is no great wonder that this happened in a few instances: approximately 12,731 B-17s were built during its production run, and most of them performed a dozen raids.

Later versions told about Major Crisp having found the ten parachutes still on-board. But an explanation was put forth later: Crisp not being an airman, he might have thought so because he saw the parachute boxes in the B-17 and failed to notice that the parachutes were not in their boxes anymore.

It was also found that the incident occurred on November 21, 1944, not November 23, 1944.

There are still some discrepancies between versions about the engines still running before, during or after landing. Most versions agree that 1 engine was off, and 3 engines were sputtering before the crew bailed out. In this case, the 3 sputtering engines may have resumed normal operation by themselves. In any case, there was no reason to see this incident as relevant to ufology.

| Date: | November 21, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Time: | ? |

| Duration: | N/A |

| First known report date: | 1973 |

| Reporting delay: | None, decades. |

| Country: | Belgium |

|---|---|

| State/Department: | Brabant |

| City or place: | Huldenberg |

| Number of alleged witnesses: | Several. |

|---|---|

| Number of known witnesses: | ? |

| Number of named witnesses: | 1 |

| Reporting channel: | Ufologist Loren E. Gross. |

|---|---|

| Visibility conditions: | ? |

| UFO observed: | No. |

| UFO arrival observed: | N/A. |

| UFO departure observed: | N/A. |

| UFO action: | N/A. |

| Witnesses action: | |

| Photographs: | No. |

| Sketch(s) by witness(es): | No. |

| Sketch(es) approved by witness(es): | No. |

| Witness(es) feelings: | |

| Witnesses interpretation: | ? |

| Sensors: |

[ ] Visual:

[ ] Airborne radar: [ ] Directional ground radar: [ ] Height finder ground radar: [ ] Photo: [ ] Film/video: [ ] EM Effects: [ ] Failures: [ ] Damages: |

|---|---|

| Hynek: | N/A. |

| Armed / unarmed: | Armed, 5 7.62 mm machine guns. |

| Reliability 1-3: | 2 |

| Strangeness 1-3: | 1 |

| ACUFO: | Explained, not UFO-related. |

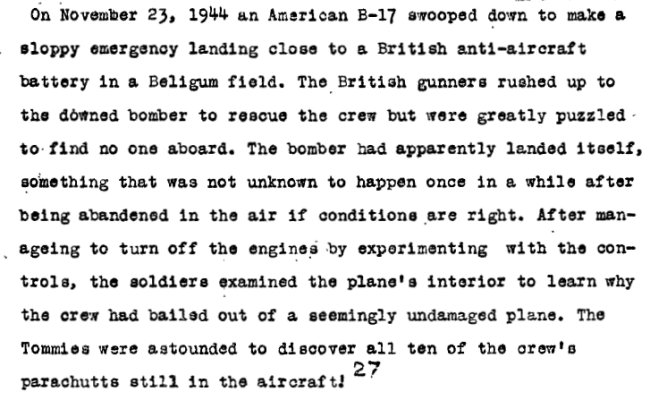

[Ref. lgs1:] LOREN GROSS:

|

On November 23, 1944 an American B-17 swooped down to make a sloppy emergency landing close to a British anti-aircraft battery in a Belgium field. The British gunners rushed up to the downed bomber to rescue the crew but were greatly puzzled to find no one aboard. The bomber had apparently landed itself, something that was not unknown to happen once in a while after being abandoned in the air if conditions are right. After many ageing to turn off the engines by experimenting with the controls, the soldiers examined the plane's interior to learn why the crew had bailed out of a seemingly undamaged plane. The Tommies were astounded to discover all ten of the crew's parachutes still in the aircraft. 27

The source “27” is not referenced in this document.

[Ref. gvo1:] GODELIEVE VAN OVERMEIRE:

1944, November 23

BELGIUM, south-west of Brussels

(source GESAG, GS 1049) Letter written by John V. Crisp, part of the entourage of a British officer, who wrote these notes during his stay at The Cottage, West-End, Essendon, Hertfordshire, England. The notes were transmitted to the authorities through the US Embassy in London: “On November 23, 1944, the men of the British anti-aircraft unit located a few miles southeast of Brussels, a B-17 Flying Fortress, approaching their firing site. It had its landing gear down and was rapidly losing speed. The British immediately called Troop Commander and almost at the same time the B 17 landed in a plowed field, near the machine guns, bouncing on the uneven ground 30 yards from the anti-aircraft position. At the last moment the tip of a wing touched the ground, sank into it, spinning the plane. The propeller of the nearest engine was thrown in the air, but the other three engines were still running. The gunners were waiting to see the crew come out and welcome them, but no one came out. They went to circle the plane and noticed no signs of life. It was at this point when the Troop Commander called me to the operations room at Erps-Kwerps near Kortenberg. Within 20 minutes I was on site examining the B-17. I had never had to deal with airplanes, but finally I could enter through an entrance under the fuselage. The plane was empty of occupants, yet traces of presence were everywhere. I got into the pilot's seat to stop the three engines which were still running, which succeeded after several attempts. On the navigator's console the logbook was open and the last words written there were “Bad Flack” (vog's note: two possible translations “bad bulletproof vest” or “bad anti-aircraft shot”). With curiosity I retraced the route which was to take the plane from the Ruhr (Germany) to Hertfordshire (England) and I wondered what could have happened to the crew. We all started searching systematically and our most extraordinary find was made in the fuselage where we found a dozen parachutes well folded and ready for use. This made the question about the crew even more mysterious. The Sperry (for tracking bombs) was still in the nose, having suffered no damage and its cover was neatly folded next to it. Behind the navigator's desk there was the Code book giving the numbers and letters of the day for identification. Several pilots' furry jackets were in the fuselage along with a few chocolate bars, some of which were partially eaten. No damage could be discovered to the B 17 apart from that of the landing. So I left directly for the 83rd Tactical Air Force in Everberg to give them my report and the B 17 logbook, several navigation charts, but the story of the landing of a B 17 empty of occupants is remained a mystery to this day. The crew was never found. (Martin Cardin [sic], Cape Kennedy, Florida, “Flying Forts” Ballantine Books inc. ed. 1968, pages 10-12).

[Ref. lhh1:] LARRY HATCH:

517: 1944/11/23 00:00 1 4:50:00 E 50:20:00 N 3331 WEU BNL BLG A:7

BELGIUM loc.unk:BRIT.AA GUNNERS:US B17 LANDS:NO CREW!:ALL 10 PARACHUTES ABOARD

Ref#129 GROSS, Loren: CHARLES FORT & UFOS Page No. 56: MIL. BASE

[Ref. chh1:] CHRISTOPHER HOITASH:

World War 2

Jan 29, 2019 Christopher Hoitash, Guest Author

On November 23, 1944, a Royal Air Force antiaircraft unit stationed outside Cortonburg, Belgium observed a B-17 Flying Fortress flying towards them. The massive U.S. Army Air Forces bomber approached at high speed with its landing gears down.

With no landing scheduled, the base personnel presumed it was an emergency landing situation and reacted accordingly. The Flying Fortress proceeded to execute that emergency landing by plowing into a nearby field.

Having just barely avoided crashing into the unit's guns, the aircraft's landing was so fast and uncontrolled that the propellers snapped off and both wings slapped into the earth during the descent. Three engines continued rumbling, and the base personnel awaited what would clearly be a rattled crew.

For over fifteen minutes the soldiers on the ground waited for the bomber crew's to appear, but no one left the damaged plane. After twenty minutes of nothing, Major John V. Crisp cautiously approached the B-17.

Lacking knowledge of the aircraft, it took him a moment to find an entry hatch. Eventually finding the hatch under the fuselage, the Major opened it and entered the bomber alone. His own words best describe what he found:

We now made a thorough search and our most remarkable find in the fuselage was about a dozen parachutes neatly wrapped and ready for clipping on. This made the whereabouts of the crew even more mysterious. The Sperry bomb-sight remained in the Perspex nose, quite undamaged, with its cover neatly folded beside it. Back on the navigator's desk was the code book giving the colours and letters of the day for identification purposes. Various fur-lined flying jackets lay in the fuselage together with a few bars of chocolate, partly consumed in some cases.

Amazingly, the B-17's crew was nowhere in sight. Not even their dead bodies remained in the bomber. The only significant clue seemed to be the last note in the codebook: “bad flak”. Despite such a message, the only damage the bomber had sustained was from its landing. More to the point, the parachutes remained, meaning if anyone did bail out, they must have done so to certain death.

The B-17 became known as the “Phantom Fortress”, and it took some time to form an idea of what might have occurred. The bomber itself was confirmed to be from the 91st Bombardment Group. The Phantom's last mission involved bombing oil refineries in Merseburg, Germany. During this mission, something went awry.

The crew, amazingly, were found to be alive and accounted for in Belgium. According to them, the bomb rack had developed a problem. When they veered away from the group to resolve the issue, they took enemy fire which further damaged the rack and took out one of the engines.

The crew then decided to head for England, but when it became clear the bomber wouldn't make it, they changed course to Brussels, Belgium. Along the way they jettisoned excess weight to keep the B-17 aloft. The Phantom continued to flounder, so the crew set the craft to autopilot and bailed out.

The crew's story did not match the evidence, as the bomber seemed to suffer none of the damage they had described. Attempts to bridge the two are reasonably plausible, though still odd.

The engines may have kicked back into working order on their own after the crew bailed. The initial investigators, lacking knowledge of aircraft and only knowing of flak damage from the exiting end, could have mistaken battle damage for crash damage.

Though plausible, neither of those theories account for the crew's parachutes remaining on board. They also cannot explain how the bomber managed the most difficult aspect of flying: landing in something resembling a single piece. The Phantom's unmanned crash landing was a first, and left many wondering just how it happened.

The best theory developed boiled down to coincidence. The bomber, losing altitude at the right speed and angle for a descent, happened to crash land in a way as only such a legendarily sturdy bomber could theoretically do.

Many theories and few answers surrounded the Phantom Fortress. None of them have been fully explained, and the bomber's unmanned landing remains one of the many strange and mysterious things that have been known to occur during warfare.

[Ref. bdg1:] BRIAN DUNNING:

This B-17 supposedly completed a mission and returned to base, all without an aircrew

by Brian Dunning

Filed under History & Pseudohistory, Paranormal, Urban Legends

World War II was among many other things the source of some of the world's greatest stories. But among these tales of adventure, heroism, sacrifice, and terror are a few other types of stories that slipped through the cracks including ghost stories. One of these concerned a famous bomber, a B-17 Flying Fortress, said to have returned from a mission over Germany, navigated back to Britain with its squadron, and then executed a perfect landing. There's nothing unusual about that; but when ground crews observed nobody getting out of the plane, they went to check on it themselves and found it empty. The B-17 had apparently flown its mission without an aircrew. Books of ghostly tales now tell the story of the Phantom Fortress, and today we're going to turn our skeptical eye upon it, and we will find out how much of the Phantom Fortress's tale is fact and how much of it is fiction.

Normally in a Skeptoid episode, here's where I'd tell the story as we hear it today. That's a bit difficult, because there are multiple versions of the story floating around. In some, the phantom plane lands in Belgium; in others it lands in Britain. In some the crew all parachute safely; in others they land behind German lines. We even have versions where meals are found half-eaten aboard the landed aircraft, recalling echœs of the Mary Celeste.

I found one apparent nexus that ties the various versions of the story together, and it's found in Martin Caidin's 1991 book “Ghosts of the Air: True Stories of Aerial Hauntings” - not an encouraging title when you're trying to dig for historical fact. Most of his chapter on this story is quoted from a letter he received in the 1980s from a man named John T. Gell, who had been a boy during World War II. On perhaps the most memorable day of the war for him, he and his family had been outside their home in Riseley, a small hamlet in North Bedfordshire, England, watching the familiar sight of American B-17 bombers returning from the day's mission over Germany. One bomber, however, its engines stuttering uncertainly, dropped low and headed right for them; moments later it crashed into the trees in their back yard! Gell's father sprang into action, searching the wreckage for injured crew members. To the family's astonishment, there had been nobody aboard at all. Gell wrote:

This B-17 had been with the 303rd Bomb Group, and then we confirmed that the entire crew had bailed out over Belgium. Yet this Fortress, now entirely unmanned, had flown in formation with the other B-17s, turning and whatever was necessary to descend and tum, directly back to its home field before crashing in our backyard. The pilots with whom I have discussed this at first flatly refused to believe it, but the factuality of it all became ever more evident when we found that not only had the entire crew bailed out, but they had all escaped from German-occupied territory and ten days later were back in the air again aboard another B-17!

Although Gell's story ends with a crash rather than a perfect landing, it does include the most incredible part of the story: the bomber flying itself along with its squadron all the way back from Belgium, a feat that would be impossible by any practical interpretation. Are we forced to conclude that some supernatural force must have been at play; or is there room to search deeper?

We have a singular advantage when researching World War II stories, and that's the war's extensive documentation - no part of it being better documented than the histories of the bomber squadrons. Every group has an association, a website, historians of its own; we know the day-to-day histories of every aircraft, every crew member, and every mission flown; and the bombers in this Phantom Fortress story are no different. Gell did record the markings on the bomber that crashed into his trees, and that made it easy to look up its actual history. It was B-17F serial number 42-5482, named the Cat o' 9 tails, attached to the 359th Bombardment Squadron of the 303rd Bombardment Group (known as the Hell's Angels), and was recorded as suffering flak damage over Germany on October 14, 1943 and finally crashing all the way back home in Riseley. Squadron records even include the detail that it crashed into trees and broke apart and was declared salvage, meaning destroyed beyond economic repair.

So far as its crew having bailed out over Belgium, that's another story. In fact, searching for such an event, I found that it's literally another story. The most popular tale of a B-17 crew bailing out over Belgium turns out to have happened to a different plane - a story that took place over a year later, but that had an ending much more in line with our ghost story. On November 21, 1944 (often wrongly given as November 23), a British anti-aircraft crew behind Allied lines in Belgium spotted a bomber and its engines sputtering coming in to land in a nearby field. It landed almost perfectly, but dragged a wingtip and spun around, a type of less-than-ideal landing called a ground loop, suffering minor damage in the process. British Major John Crisp, fearful that it might be some kind of German booby trap, carefully climbed aboard even as its engines were still running. He found it absolutely deserted, and shut the engines off himself. This one was a B-17G, serial number 43-38545, attached to the 401st Bombardment Squadron of the 91st Bombardment Group, a famous group dubbed the Ragged Irregulars.

So it appears that we end up with two similar but distinct stories: different years, different planes, different countries; but that appear to have woven themselves together into one, once we leave the authoritative historical texts and move into the realm of mass-market publications. That nexus published in Caidin's ghost story book appears to be the key.

When John Gell wrote his letter to Caidin with his account of the uncrewed plane flying from Belgium to England, some forty years had passed. The story of the plane that ground looped in Belgium had been printed in the Stars ∧ Stripes newspaper and from there had been syndicated throughout the Allied countries. It had become a reasonably well-known legend, variously dubbed the “Ghost Ship” or the “Phantom Fort” by the press. Forty years later, it is entirely reasonable for Gell to assume the famous plane that crashed with no one on board was the very one that had actually happened right before his eyes when he'd been a boy and, just to be clear, the crash at the Gell home is an absolute historical fact, as it's where the Americans had come to retrieve the wreckage, 170 High Street in Riseley. Gell made nothing up, but he does appear to have understandably and accidentally conflated these two events; and thus intertwined, the beginning of one aircraft's story grafted onto the end of the other one's was a ghost story so good that Caidin could not help but include it in his 1991 book.

The plane that crashed into the Gells' yard had just participated in a bombing raid which became known as Black Thursday, both for the number of crews lost to enemy action, and for those lost due to bad weather over the bases in Britain. The B-17F Cat o' 9 tails, captained by 21-year-old 2Lt. Ambrose G. Grant, was substantially but not fatally damaged by German flak, and Grant was able to fly it all the way back across the Channel to their base at Molesworth along with the rest of the squadron. However, his instruments had all been destroyed and he was unable to find Molesworth's lights in the dense fog, and they were critically low on fuel. Grant ascended to 7,500 feet and all ten crew members bailed out, and when the plane crashed into the Gells' trees at 6:40pm, all ten landed safely about four miles away. It was, in fact, an all-too-common event in those days; no ghosts needed to explain it. Ironically, a mere three weeks later, Grant and his crew were shot down over Germany and spent the rest of the war in a Luftwaffe POW camp.

A year later and 250 miles away, 28-year-old 1Lt. Harold R. DeBolt was in command of a B-17G that was almost brand new, having flown only two previous missions, and had not yet been given a name. This was its first flight with this squadron, having just been transferred from the 324th. But being new did not protect it from the German anti-aircraft artillery. DeBolt had been unable to complete his bomb run over Merseburg, Germany due to damaged bomb bay doors and a massive explosion of flak right beneath them. With two engines out and a severe vibration threatening to destroy the airframe, DeBolt soon realized it would be impossible to make it back to Britain and instead headed for the Allied lines in Belgium. They managed to still have a safe altitude of 2,000 feet by the time they crossed into friendly territory, and all nine crewmen parachuted to safety and were soon rescued by British troops. DeBolt had left the fatally wounded B-17 on autopilot, as was the standard procedure when leaving the controls in order to bail out. The autopilot kept it on the straight and level as it continued to descend, and it then made its rough landing in the field where Major Crisp found it. The uncrewed landing was pretty neat, but it was hardly bizarre or inexplicable.

Take a piece from Grant's story and another from DeBolt's, connect them together, and fabricate a new story that tells of a miraculous and unexplainable sensation, and you've got today's Phantom Fortress story.

The tale of the Phantom Fortress, presented in the mass media and on the Internet as a mystery that cannot be explained, is a typical one. It required comparatively little research to discover that Gell's account as published in Caidin's book of ghost stories included some obvious errors. That very same research yielded the building blocks from which the Caidin version was assembled, and those blocks were each stamped with the serial numbers revealing which of the two B-17 stories they came from. If you take any similar “amazing” story from pop culture, chances are that you'll find some such mistake or error in its building blocks as well. Actual events can never be unexplainable, by definition; if they actually happened, there's an explanation, even if it's not immediately apparent.

Although an incredible story like a phantom B-17 that completes a mission and lands all by itself with nobody at the controls is cool, it should hardly be satisfying to stop there and not want to learn more. Apply the tools of critical thinking, and you'll have the common pleasure of enjoying the mystery story, plus the all-too-rare bonus of actually solving it.

References & Further Reading

303rdbg.com. “303rd BG (H) Combat Mission No. 78.” Hell's Angels: 303rd Bomb Group (H). 303rdbg.com, 10 May 2006. Web. 18 Aug. 2020. http://www.303rdbg.com/missionreports/078.pdf

91stbombgroup.com. “The Ghost Ship.” 91st Bomb Group (H). 91st Bomb Group.com, 25 Nov. 2011. Web. 14 Aug. 2020. http://www.91stbombgroup.com/91st_tales/58_the_ghost_ship.pdf

Caidin, M. Ghosts of the Air: True Stories of Aerial Hauntings. New York: Bantam Books, 1991. 139-149.

Hoitash, C. “Phantom Fortress: The Crewless Landing of a B-17.” War History Online. Timera Media, 29 Jan. 2019. Web. 16 Aug. 2020. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/phantom-fortress-b-17.html

Osborne, D. B-17 Fortress Master Log. London: Dave Osborne, 2011. 124.

Zhou, J. “B-17 42-5482 / Cat-O-Nine Tails.” B-17 Flying Fortress. Jing Zhou, 16 Mar. 2018. Web. 18 Aug. 2020. https://b17flyingfortress.de/en/b17/42-5482-cat-o-nine-tails

Zhou, J. “B-17 43-38545.” B-17 Flying Fortress. Jing Zhou, 27 Sep. 2019. Web. 18 Aug. 2020. https://b17flyingfortress.de/en/b17/43-38545

[Ref. aye1:] ALVA YAFFE:

Human Stories | By Alva Yaffe

Some of the greatest battles in history were held during World War II, and of those battles were those that occurred in the air. The story of the B-17 “Ghost Bomber” incident was definitely one of a kind, and its explanation is still debated today. The Ghost Bomber was an American fighter plane that essentially landed itself. And when investigators were finally able to board the mysterious aircraft, they were left only with more questions than answers. Nothing prepared them for what they were about to find out. This story of the mysterious fighter plane led to other inexplicable events that have yet to be explained.

Something happened on November 23, 1944, at an allied base in Cortonburg, Belgium that still hasn't been entirely clarified. It was on that day that an American B-17G bomber plane was heading towards three allied anti-aircraft gun positions, and from the looks of it, it was going to crash right into them. Soldiers on the ground saw that the bomber's landing gear was down, and according to the manner in which it was flying, they assumed the plane was damaged or that some of the crew members were wounded. The 35,000-pound plane was heading down fast, literally falling from the sky. and so, the soldiers on the ground braced for impact.

But No One Emerged

The plane barely struck the gun positions and hit the ground. The force was so strong that it caused the giant bomber to bounce, with the plane getting off-kilter and one of the wings ended up smashing into the earth. The propellers were breaking and they were being violently flung through the air.

The bomber finally came to a stop at around 100 feet from the gun position. The engines on the plane that were working kept running and the witnesses that were watching held their breath in anticipation, waiting for the crew to exit the plane and reveal themselves. They waited for crew members to climb out, but no one emerged. The soldiers only had one question: Where is the crew?

Deciding to Investigate

The witnesses that were on the ground watching the whole thing develop before their eyes didn't know what to think nor did they know how to help. What could you possibly do in a situation like that? Run towards the crashing plane? There was no emergency call announcing its arrival. After time passed and none of the crew emerged, people knew something was fishy.

The plane stood there in the field with its three remaining engines continuing to run and make a heck of a lot of noise. Then, after 20 minutes or so, British Major John V. Crisp decided to go ahead and investigate the scene. But Crisp was admittedly nervous and extremely cautious as he approached the aircraft.

Entering the Plane

The anticipation was growing as people were watching Major Hohn V. Crisp approach the plane. There was still no movement and no sign of life at all. Major Crisp started his investigation by searching the exterior of the plane. Since he wasn't an airman by any means, it took him a moment to find the entrance to the plane.

Major Crisp, an officer in the British Army, decided that it was going to take a while, so he set up camp nearby along with the rest of his unit. He set out alone to investigate. It took him a few moments to locate the entry hatch below the fuselage. He wasn't at all aware of what would come of this moment...

Not a Soul

Major Crisp was apprehensive about what had happened on the plane and he expected to find dead or dying men inside. It was his only explanation for why no one had exited the plane. He kept looking through the aircraft that usually held most of the ten crew members of a typical B-17G.

The Major did find signs of life, albeit they were half-eaten chocolate bars. He later commented that he was able to find evidence of fairly recent occupation everywhere, but he didn't find any human beings inside. What he did find in the plane, however, were twelve parachute packs that hadn't been used. This part of the puzzle only added to the mysteriousness of a man-less aircraft.

“The Phantom Fortress”

Major Crisp was the only person that went on board while searching for clues as to what happened to this mysterious plane. He made his way through the bomber and up to the cockpit but didn't notice anything suspicious. It seemed to Major Crisp as though the plane had somehow managed to not only fly itself in the air, but land itself too!

Major Crisp was able to finally turn off the engines of the plane, as they were still running. He found the aircraft's log and noticed some scribblings on it. But the lack of crew on the bomber remained the most puzzling part. Where was the crew? What happened to them? How does a plane land itself?

The investigation would eventually lead to headlines of “The Phantom Fortress” circulating everywhere...

An Immediate Inspection

The incident and its inherent mysteriousness were sent through the chain of command, and an investigation began immediately as the commanders had heard everything and thus feared the worst. To make matters even more complicated, the B-17G that seemingly landed itself also didn't even have a name. How bizarre is that?

Investigators arrived at the scene and found the plane's serial number, which allowed the commanders of the 8th Air Force to finally identify the plane as being part of the 91st Bomber Group. The 91 st Bomber Group was a group of B-17Gs that operated out of East Anglia, England. As they discovered, the plane did indeed take off with its crew, but where exactly the crew disappeared to was the head-scratcher...

Locating the Crew

Once the plane was identified as the 91st Bomber Group, new questions were starting to be asked. The plane was full of evidence that there were definitely members on board, at least at one point. Also, the cover to the Sperry bombsite was removed, which was a typical practice when a fighter plane was on a bombing run.

The 12 parachutes that were still sitting on the plane were a big part of the puzzle. Despite the parachutes being on board, the only assumption that could have been made was that the crew jumped out with no equipment. The crew was eventually found. All ten men were alive and well at an airbase in Belgium. But they had some answering to do...

Their Mission

According to the crew members that were surprisingly found alive, their assigned mission was to bomb the Leuna oil refinery in Merseburg, Germany because it was marked as a dangerous target. By that point in the war, allies had been aiming at and hitting German targets non-stop.

The British army was bombing German targets by night, while American bomber crews from England and Italy were bombing German targets during the day. Bombing accuracy was a real problem as well, so American war planners insisted on daylight missions for the attacks that required more precise airstrikes. In the end, day strikes only meant that American bombers were more vulnerable since they could easily be seen.

A Direct Hit

Lt. Harold R. DeBolt, the pilot of the B-17G, was an experienced pilot. The bomber was making its way to Germany just fine until the group started its bombing run. At a certain point, the plane was unable to keep its altitude with the rest of the group.

That's exactly the point when German anti-aircraft took the opportunity to open fire on the low-flying bomber, and it hit the plane twice. The plane sustained a direct hit, but somehow it didn't set off any of the bombs. “We had been hit in the bomb bay,” said Lt. DeBolt. “I'll be darned if I know why the bombs didn't explode.

The pilot only had to decide what he was going to do next...

They Abandoned the Bombing Run

One of the plane's engines was damaged by a direct flak hit, which may seem bizarre considering the fact that all four engines were still functioning when it landed. The bomber's crew knew that they were in trouble when they were flying really low, frighteningly alone, and over enemy territory nonetheless.

To make matters worse, the weather at the time was terrible, and the plane was experiencing a lot of turbulence as they were flying through the clouds. At that point, an engine was knocked out, and the bomb bay was malfunctioning. So, Lt. DeBolt had to make a quick decision, and he decided to have the crew abandon the bombing run and head the bomber back to his base in England.

A Decision to Ditch

Lt. DeBolt was doing his best and added as much power as he could to the engines, but the plane was slowly losing altitude. He did what he thought he had to do: he ordered the crew to dump all loose equipment. They did as he ordered, but the plane was still falling.

The crew was hoping that the plane would make it back to their base, but as time was quickly passing, so were their hopes. Suddenly, a second engine stopped turning, which left Lt. DeBolt with no choice; he was going to need to give the order to ditch the vessel. He directed the plane on a course toward Brussels. He commanded the crew to get their parachutes ready...

They Jumped Ship (or Plane Rather)

Once the plane was hit, pilot Harold R. DeBolt had to turn the bomber around and head back in the direction of England. But when the plane's second engine was compromised, DeBolt became aware of the fact that the plane simply wouldn't make it across the English Channel.

After setting the plane toward Belgium, the plan was for the crew to bail the aircraft. DeBolt, being the pilot, was the last to leave. He had to set the plane to function on autopilot and then he jumped. The crew did what they had to do, but they didn't know what would happen to the plane. They anticipated that the plane would eventually just crash into the ground.

On Auto-Pilot

Apparently, there had been reports of planes flying by themselves during the years and battles of WWII, but a B-17G bomber plane that was remaining on two working engines had little to no chance of staying in the air. The crew, after jumping out, watched as the plane flew away. Then a thick cloud caused them to lose sight of it. The plane was still in the air as they were making their way to the ground.

Incredibly, the plane managed to fly for miles on its own on only a half-engine capacity. The captain reported to his superiors that they ditched the aircraft near Brussels, Belgium. But all that still wasn't enough information for investigators who were working on the case...

The Biggest Part of the Puzzle

How do you explain a situation in which there is a crew without parachutes and a plane that somehow flew alone for miles on wounded and insufficient engines? There were major discrepancies and holes in the story, as well as in the investigation report. It was all very unclear. But there was still the most puzzling part of the whole equation.

How the plane managed to go so far in its conditions and still manage to land on its own was too strange for anyone to understand. Especially considering the fact that there was bad weather - it's all a mind-blowing concept. No one understood how the plane landed. Any pilot would have said, and did say, that it's simply impossible.

A Case of Conflicting Reports

There were even more conflicting reports in the ghost bomber case. There were confusing reports about what the soldiers on the ground saw when the plane landed. The crew's version of events before they aborted their bombing mission were incompatible. The crew had reported that one engine was destroyed, and one quit.

WWII: America: Army in England: American parachute troops are now in this country and have already been engaged in invasion exercises. The picture shows: An American paratrooper just landed, has his rifle ready for action as he spills the wind from his parachute. Photo By Northcliffe Collection/ANL/Shutterstock

But, despite those reports from the crew, according to the soldiers on the ground, all four of the engines were intact (until one was finally destroyed on landing). Both accounts, from the crew as well as the soldiers on the ground, were recorded in the official investigation, but the contradiction was still never resolved. Was there a hole in the crew's story or the soldiers on the ground?

Not Properly Trained?

Yet even more discrepancies existed in the reports. Another discrepancy in the reports was that the crew reported that they were struck by enemy fire, which is the reason why they aborted the plane. But Major Crisp and the other soldiers had reported that there was no damage on the plane that would support the crew's claim of enemy fire.

There is a possible explanation for this discrepancy, and that is that Major Crisp, as well as the other soldiers, weren't trained well enough to identify what the difference is between damage that occurs from enemy fire and damage that is sustained by a rough landing. And this lack of knowledge could potentially explain the difference in their reports.

Were the Parachutes on Board?

It's still a very bizarre thing that Major Crisp found all those parachutes on the bomber. Not just that they were on the plane, but that they were also still intact. While it is understandable that the crew would need to abort the mission due to enemy fire being directed at them, it isn't plausible that the crew would be able to abort the plane without parachutes.

Unfortunately, the official report never did resolve this discrepancy. So, essentially, we might never know why the crew left the parachutes behind. It is also remotely possible that Major Crisp saw the 12 parachute packs that were in fact used and just had didn't have the parachutes inside them. Maybe Major Crisp didn't open up the parachute packs to see.

A Tough Plane

The B-17G ghost bomber was a sturdy airplane. It was made to be able to sustain a substantial amount of damage that could happen in war. Lt. Debolt may have made the decision that was best for his crew, but the truth is that his plane was also doing lots of the necessary work that was needed to keep everyone alive.

The B-17 in this photo is another plane that did its job. As you can see, there is considerable damage that occurred. With the damage absorbed on its left engine and only one and a half wings, the bomber still managed to land. But this particular plane had a pilot and a crew who physically brought it in for landing.

Was it a Miracle?

The way this mysterious ghost bomber went down was really and luckily the best-case scenario. It could have been so much worse. The crew ended up making it out safely and the plane didn't cause any further destruction as it flew on and eventually made its way down to the ground.

There were many other stories during World War II that didn't end so well. There are tons of occurrences from the war in which several aircrews encountered incidences without any logical explanation. Let's take a look at a few...

The U.S. B-17 “Flying Fortress” was a heavy bomber fitted with five 7.62 machine guns for its defense against enemy fighter planes.

|

|

History sources are quite clear about all of this.

The “first” incident, described in [bdg1], is about B-17 42-5482 nicknamed “Cat o' 9 tails”, of the 359th Bombardment Squadron of the 303rd Bombardment Group, based at RAF Molesworth when it sustained flak damage over Schweinfurt on October 14, 1943. The crew was pilot: Ambrose Grant, co-pilot: Franklin Ball, navigator: Jim Berger, bombardier: Marion Blackburn, Flight engineer and top turret gunner: Tony Kujawa, radio operator: Ed Sexton, ball turret gunner: Chester Petrosky, waist gunners: Bob Jaouen and Woodrow Greenlee, tail gunner: Francis Anderson The crew bailed near the coast and the B-17 crash landed in Riseley, near Molesworth. It broke in half after hitting tree. (Main source is the book The B-17 Flying Fortress Story by Roger Anthony Freeman and David R. Osborne, 2000.)

In this incident, as stated in [bgd1], there is nothing out of the ordinary at all.

The “real” Phantom Fortress incident relates to B-17 43-38545 later nicknamed “The Queen Of The Skies” of the 401st Bombardment Squadron of the 91st Bombardment Group, based at RAF Bassingbourn and battle damaged on November 21, 1944, during its raid on the Synthetic Oil Plant of Merseburg, Germany. The crew was 1st Lt. Harry R. DeBolt as first pilot on his 33rd mission, Major Klette as navigator, Osborne Stone, Bill Dominguez, Dick Cusson, Troy Young, John Alba, Granville Houchins, Chas Walker, Nelson Richardson.

The History of the 91st Bomb Group (www.91stbombgroup.com) indicates that in the raid, with bomb bay doors open, DeBolt's aircraft stalled and dropped out of formation, and it was at this instant attacked by enemy fighters and also began the run through a very heavy and accurate flak barrage. Due to malfunction with the bomb release mechanism, the bombs would not drop, and this caused the aircraft to fall further out of formation. About this time the whole ship took the blast from a flak burst just below the bomb bays.

The explosion caused the bombs to drop but No. 2 engine was completely out and No. 3 engine was badly milling and causing undue vibration throughout the aircraft, this being caused by flak damages. At 1500 feet the other two engines failed. The crew began jettisoning all surplus equipment in an effort to lighten the Fortress as DeBolt set course for home. The plane was losing altitude and was turned to a heading of 270 degrees west, for friendly lines. The crew stayed with the plane as long as they could and when it was down to 2,000 feet, Hal gave the signal for everyone to “bail-out” and they did, while the Fort continued on its way with the autopilot doing its job. All chutes opened and the men were picked up by British infantrymen soon after landing.

The damaged Fortress continued onward, losing altitude and remaining in a perfect landing attitude. The Fortress mysteriously made a perfect three point landing in a plowed field. It ground looped at the end of the field and sat there with engines still running, undamaged in an open field, in Huldenberg, about 10 miles east of Brussels, near Liege, Belgium, not far from a British Anti-Aircraft Artillery site. The landing was in a flat strip area, near a British Army encampment. A British Officer ran out to help the crew, but only found neatly stacked flying gear inside and was astonished to find no one on board. He inspected the Fort (as a possible German trap) but found no one. He then turned off the operating engines. The British Officers name was Major John Crisp.

The B-17 was salvaged. Stars and Stripes magazine published the story on December 8, 1944, calling DeBolt's B-17 a “Ghost Ship“, or “Phantom Fort”.

Explained, not UFO-related.

* = Source is available to me.

? = Source I am told about but could not get so far. Help needed.

| Main author: | Patrick Gross |

|---|---|

| Contributors: | None |

| Reviewers: | None |

| Editor: | Patrick Gross |

| Version: | Create/changed by: | Date: | Description: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | Patrick Gross | April 15, 2024 | Creation, [lgs1], [gvo1], [lhh1], [chh1], [bdg1], [aye1]. |

| 1.0 | Patrick Gross | April 15, 2024 | First published. |