The Tagish Lake meteorite fell to Earth in the Yukon Territory in Canada on January 18, 2000. When found, the meteorite was collected and kept frozen with the highest level of precautions ever; which ensured that it did not become contaminated by any terrestrial sources.

Researchers extensively tested the meteorite using electron microscopes and quickly found numerous hollow, bubble-like organic hydrocarbon globules in the meteorite. It is thought that these organic globules, the first found in any natural extraterrestrial sample, are very similar to those produced in laboratory simulations designed to recreate the initial conditions present when life first formed in the universe, and constitute possible precursors to early extraterrestrial life.

This previously unseen type of primitive organic material was formed long before our own solar system came into being.

A team of five researchers collaborated on a two-year study of the meteorite. The team was led by Keiko Nakamura of Kobe University in Japan, who was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Nakamura is now working at JSC under a postdoctoral grant from the U.S. National Research Council. Co-authors of the study include Zolensky, who was funded by the NASA Cosmochemistry Program; Satoshi Tomita and Kazushige Tomeoka, both of Kobe University, who were funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, respectively; and Satoru Nakashima of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who was also funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

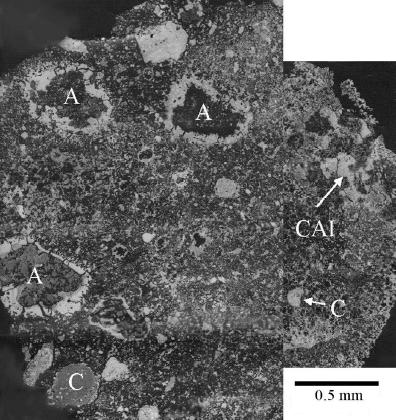

Below:

Electron microscope images from two fragments of the meteorite. (C) are chondrules, (A) are olivine agregates, indicative of liquid water action, (CAl) is a calcium/aluminum rich area, opaque areas are magnetite.

|

Dr. Michael Zolensky, an author of the paper about the finding in the Astrobiology Magazine, and a researcher in the Office of Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, stated:

"While not of biological origin themselves, these globules would have served very well to protect and nurture primitive organisms on Earth, they would have been ready-made homes for early life forms."

The numerous small holes of this meteorite is also so fragile that it is great luck that it did not burst in parts when it entered into Earth's atmosphere. This type of rocks normally are torn apart during reentry and the debris are scattered over a large area.

Zolensky said:

"If, as we suspect, this type of meteorite has been falling onto Earth throughout its entire history, then the Earth was provided with these hydrocarbon globules at the same time life was first forming here. We were exceedingly fortunate that this particular meteorite was so large that some pieces survived to be recovered on the ground."

In 2001, researchers at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, announced that they had made basically identical hydrocarbon globules in the laboratory from materials present in the early solar system and interstellar space.

Zolensky said:

"What we have now shown is that that these globules were in fact made naturally in the early solar system, and have been falling to Earth throughout time."

The researchers believe the Tagish Lake meteorite came from the outer asteroid belt, toward Jupiter, and that similar organic materials may have been falling onto the moons of Jupiter, including Europa.

Zolensky said:

"It is interesting to speculate about the presence of these organics in the ocean we believe may be present under the ice cap of this moon."